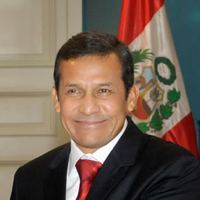

In June 2011, Ollanta Humala was elected president of Peru after campaigning on a platform of change. Significant for Peru, but also for South America more broadly, Humala advocated for moderate, not revolutionary, change -- calling for a better and fairer distribution of the fruits of Peru's impressive economic growth and for lower levels of corruption and crime. That kind of program won't entail upending the prevailing system. It will, however, require serious institutional reform.

The Peruvian case dramatically illustrates wider trends in South America, where sustained economic growth and sound macroeconomic policymaking in recent years have coexisted with continuing governance challenges. Peru has not only been one of South America's top economic performers over the past decade. The Andean nation has also witnessed a drop in poverty levels, from more than 50 percent in the early 2000s to just more than 30 percent in 2010. Studies show that even the disparity between the rich and poor has narrowed somewhat.

Yet, since taking office in July, Humala has wisely insisted on making "social inclusion" in Peru a priority. The term, which has growing resonance throughout the continent, is defined not only in terms of reduced poverty and inequality, but also, significantly, in terms of increased political participation and wider access to economic opportunities. On these scores Peru has fared considerably less well, giving rise to profound distrust of political institutions and pervasive discontent, which Humala skillfully tapped into during his election campaign. The dissatisfaction is particularly acute in the southern highlands of Peru, where the country's important indigenous population is concentrated.